Dear Reader,

Here is part II of my conversation with Suzanne Schneider, an historian and political theorist of the modern Middle East. You can read part I of our conversation here.

We discuss the different factions on the Left, antisemitism, imperialism, the possibilities of a one-state or two-state solution, what to read right now if you’re looking to learn more about the history of Israel and Palestine, and grief.

And Suzanne just started her own Substack, Dr. Small Talk! Please follow her.

Until soon.

Sam

What is happening on the left right now? What do you make of the political movement that has emerged? We’re seeing mass protests against Israel. Mass protests for Palestinian liberation. Why are some people defending Hamas? Why are some people calling for a ceasefire? Can you break down the political factions that have formed?

As far as I can tell, the left is very divided in ways that I see as catastrophic.

I think this recent piece in New York magazine does a good job of reviewing some of the major points of contention, and I am frankly a bit worried of belaboring them given how tiny the left is as an organized force.

I will say that I think those truly celebrating Hamas in the West are few and far between, and highly concentrated among the very online which tends to amplify their voices. But still I was shocked by how many were willing to make what Edward Said called the “devil’s pact” with Hamas, again both on ethical and strategic grounds. Given the decades-long attempt to discredit anti-Zionism as antisemitism, perhaps throwing one’s weight behind an organization that cites the Protocols of the Elders of Zion in its founding charter was not the wisest choice? However few, the existence of these voices is excellent fodder for the Zionist right and has been successfully used to steer liberals toward embracing the position that Jews are everywhere hated, isolated, no one cares about our suffering, so on, and thus a nuclear nation-state is the only way to achieve security.

Looking at the remainder of left-liberal forces, we find several gradations once we leave the edgelords: those who don’t necessarily endorse Hamas but who frame the October 7th attacks as legitimate acts of resistance by an occupied people using any means necessary. This position often comes off as a shrug of indifference toward Israeli victims—“This is what decolonization looks like”—as they believe that armed struggle is the only way to achieve justice and freedom for the Palestinians.

These people have not, I would contend, thought nearly enough about the limits of the settler-colonial framework or the efficacy of armed struggle in this context. Rashid Khalidi, who does use the settler-colonial framework, has underscored how any victorious strategy is going to have to move public opinion in the metropole – i.e. in the United States, and I don’t see that happening with Hamas at the helm. The idea that liberation is inevitably waiting at the end of this very bloody rainbow reeks of a naïve Hegelian faith in the spirit of history, and I don’t put much stock in the inevitability of progress.

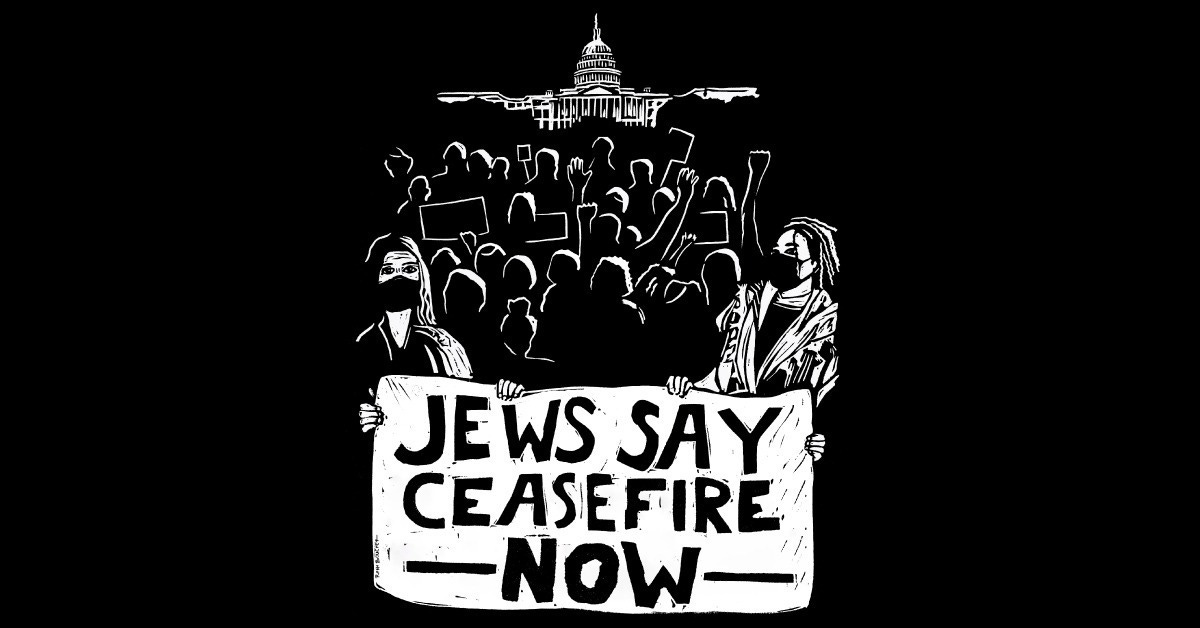

Next you have the masses of people who probably do not know the intricacies of the conflict, but who understand enough about Israel’s longstanding practices of apartheid, occupation, and dispossession to stand with the Palestinians. I think this characterizes most people out in the streets at this point. They might think it is commonsensical to separate Hamas from the Palestinian people and that it’s possible to support the latter without the former, but have tended not to pay much attention to the Israeli victims and hostages. I think many would say, and not unreasonably, that people have limited capacity and attention spans and to focus on what happened on October 7th while Israeli forces are killing a Palestinian child every 15 minutes is to not have one’s priorities in order.

Further along you have liberals who oppose the occupation, probably support a two-state solution, but also have been lukewarm on things like BDS, conditional aid for Israel, or any other diplomatic or grassroots strategy to compel a meaningful political shift. They feel abandoned by the organized left’s seeming indifference toward Israelis who were killed, raped, and kidnapped, and scared by the reluctance to root out antisemitism in the Palestine solidarity movement. I think a lot of American Jews fit into this bucket, and they have tended to break right or stay on the sidelines. I don’t see any meaningful shift in American support for Israel coming about without moving this group of people, and you aren’t going to do it by trivializing Jewish suffering or fear.

Nothing about violence is inherently left – nor about nationalism and certainly not Islamist politics.

I will add that I’m also concerned about the smuggling in of ideas that I think are quite conservative and reactionary into the left under the guise of anti-colonialism. Nothing about violence is inherently left – nor about nationalism and certainly not Islamist politics. Much as I admire Edward Said’s work, I’ve been thinking a lot in recent days about the critique of it by Aijaz Ahmad, which asked “why it is that Said’s procedures turn out to be so appropriable for conservative, Right-wing positions” that trade in ideas of essentialized identity, authenticity, mystification and the like. There’s much more to say on this note, but it will have to wait.

As for a ceasefire, there are a lot of compelling reasons to support one if you don’t already. The first is that while Hamas is not necessarily winning the war, Israel is losing it. Israeli war crimes have been committed daily for all the world to see – from besieging hospitals (The search for Hamas’s secret underground lair under al-Shifa hospital is starting to feel a lot like looking for those WMDs in Iraq.) to withholding of food, water, and fuel to over two million civilians. There is no apparent strategy for the day after, no long-term political plan as to who will govern Gaza, and—despite the recent progress on this front—Netanyahu’s government has been quite clear that the hostages are not the top priority. Instead, government speaks of destroying Hamas as its primary war aim - something that no sensible political strategist thinks can be done. Sure, you can fill in tunnels and destroy arms, but you won’t destroy the source of frustration that feeds armed struggle. It’s like you have a screw that needs to come out, and instead of picking up a drill, you continue to hit it with a hammer.

Hamas’s secret underground lair under al-Shifa hospital is starting to feel a lot like looking for those WMDs in Iraq.

So, if you’re not swayed on ethical, humanitarian grounds, I would invite you to consider the case on strategic grounds and ask what precisely is being accomplished at present?

The mass slaughter of civilians doesn’t bring the hostages home or move us any closer to a political solution. I made some family members very angry a few weeks back by comparing the situation to the cult of Moloch, which is associated in the Hebrew Bible with child sacrifice. But honestly, the language of sacrifice might be too generous because it assumes that one is achieving some greater good. What we have instead, to riff on my friend Patrick Blanchfield, is pure waste.

Let’s talk about antisemitism. Can you walk us through the history of antisemitism in relation to what happened on October 7th? Why do some people argue that it is antisemitic to critique Israel? Why do people conflate the Jewish people with the nation-state of Israel? What are the consequences of that conflation?

As someone who has always insisted on differentiating between anti-Zionism and antisemitism, I have been disheartened to see that distinction stretched to a breaking point. The examples are well-known at this point – from “gas the Jews” chants at an Australia rally and protest signs playing on antisemitic tropes to vandalism, assaults on Jews and attacks on synagogues from New York to Berlin and Tunisia. Someone threw a cup of coffee on my friend’s 11-year-old son (who was wearing a kippah) in a Manhattan bodega a few weeks back. It’s pretty bleak when kids don’t feel safe wearing a kippah on the Upper West Side of all places, and I don’t think we do anyone any favors by refusing to treat antisemitism seriously.

People on both the right and left are trying to pretend that antisemitism is a problem, but only on the other side. We need to be more intellectually honest and grapple with it from all directions, and also attend to the cases that are more ambiguous.

It is important to note, however, that the uptick in antisemitism is not merely the work of the left as it’s usually presented, and it’s been encouraging to see Palestine solidarity leaders renounce antisemitism that occurs at marches or elsewhere. We also know that far-right, white nationalist forces are trying to affix themselves to this movement (see more reporting on that trend here), less in an attempt to discredit the Palestinian cause, than in hopes to push their views into the mainstream. There’s also this sort of funhouse mirror effect where right-wing Zionists like Yoram Hazony (who I’ve written about at length elsewhere) take it upon themselves to defend Elon Musk for sharing blatantly antisemitic material. People on both the right and left are trying to pretend that antisemitism is a problem, but only on the other side. We need to be more intellectually honest and grapple with it from all directions, and also attend to the cases that are more ambiguous. Not everything is as clear-cut as spray-painting swastikas on a synagogue.

Take some of the slogans being chanted at rallies. “From the river to the sea, Palestine will be free” is the most commented upon, and many well-meaning people have argued that it has nothing to do with expelling Jews from the land of Israel, but with creating freedom and equality for all across the whole of historic Palestine. Still, slogans are vague enough to encompass a wide range of substantive views – from freedom and equality for all (yay!) to something much darker that should scare us frankly. As Dov Waxman noted recently, it’s really about who is using it and what they mean. “If it's invoked by supporters of Hamas, for example, [the chant] has a very different meaning, and I would understand that as much more threatening than if it was advocated by, say, Rashida Tlaib.” And I guess that’s why I’m very tired of slogans and keep pushing for specific, boringly detailed visions of what people mean by ‘freedom’ or ‘liberation’.

Finally, I’ll add that there is a theoretical question here that has huge implications for how one thinks about the state of Israel: Is Zionism the result of antisemitism or the cause?

Scholars of Zionism tend to argue the former – that antisemitism was one of the chief forces that spurred the Jewish nationalist movement in late nineteenth century Europe. Today, on the other hand, many argue that Israel’s actions are the cause of growing antisemitism on the global stage - that by presenting itself as the Jewish state, it invites an elision between Israeli Jews and those in the diaspora. This seems borne out by empirical evidence over the last several decades, but I’m not entirely convinced. The elision between Israelis and Jews in fact requires two things: the promotion of this idea by Zionists, and the acceptance of it by non-Jews. Why is the latter so easy to achieve? It seems that there is an existing cesspool of antisemitic ideas about dual loyalties, secret networks, Netanyahu as the puppet master, and so on that circulate and that Israel’s actions are filtered through. I guess this is all a very long-winded way of saying I tend to think about antisemitism in dialectical terms – antisemitism has fueled Zionism for well over a century, but Israel’s actions now seem to give new life to the former, and so on in a very ugly cycle.

In Hannah Arendt’s 1944 essay “Zionism Reconsidered” she argued that antisemitism was a weapon of imperialism, and that as long as imperialism—expansionism, as she defined it—was at the core of the nation-state, the Jewish people would never be safe, especially in Israel. Can you talk to us about the history of Israel as a nation-state in this context?

There is a seeming paradox in that the nation-state appears as both cause and purported solution to modern antisemitism.

Let me clarify. The sort of ethnonationalism that emerged in 19th century Europe could not accommodate the Jew within the romantic framework of the volk (the people), with its emphasis on an essential, mystical connection between a particular people and territory. That’s why for all their struggles, Jews have flourished in the United States – a country that is not a nation-state in the European sense of mandated correspondence between ethnic group, territory, and government.

Unlike many Israeli politicians and Jews more broadly today, many early Zionist thinkers saw that the persecution they faced in Europe was not the mere continuum of the sort of theological Jew-hatred of prior eras, but a distinctly modern, ‘scientific’ sort of phenomenon. Many also understood that there was an economic component to modern antisemitism, and posited that it would inevitably appear wherever Jews lived in significant numbers. I think most serious scholars try to attend to the distinction between modern antisemitism and its predecessor forms—as Arendt did—but there is a strong communal impulse to regard it as one long story where only the characters change. “In every generation they rise up to destroy us, but the Holy One Blessed be He rescues us from their hands.” Jews have recited this line at the Passover seder for centuries – and you can imagine that many who do so today just slot the Palestinians into the formula. This sort of essentialism may have rhetorical power, but its poison for historians and political analysts. It feeds an ever-present temptation to pathologize the enemy instead of understanding the sources of enmity.

Now, Zionism was supposed to solve the antisemitism problem by ‘normalizing’ the Jewish people along the lines of a nineteenth century nation-state. Freed of discriminatory legislation, quotas, restrictions on professions and land ownership, Jews could finally become like all the other nations. This is why there is such a veneration of agricultural labor among early Zionists – because it marked the restoration of the stereotypical city-dwelling, over-educated, neurotic Jew to nature (on this note I highly recommend Eric Zakim’s excellent book). But we must stop and think about the limitations of the nation-state as a solution to the Jewish question. Perhaps if Palestine were truly a vacant land it would have been possible, but this was most assuredly not the case. And thus the Jewish problem is “solved,” as Arendt wryly noted, by the expulsion and dispersion of 750,000 Palestinians, turning another people into a “problem” in need of solving.

I have to say I find the logic of the nation-state horrifying, and also the rapidity with which it has taken root in our imaginations as the only possible form of political community. It really is worth underscoring that states have assumed all sorts of forms throughout history rather than treating nationalism as some sort of inherent way of seeing the world or organizing political communities. And for Jews, I think the logic of nationalism is quite dangerous both for those of us in the diaspora and those in Israel, though for different reasons.

Think of the hundreds of thousands of Jews who were expelled from their homelands in Arab countries in the years after the founding of the state of Israel – their dual identity as Arab and Jewish became impossible not just in the context of Zionism, but Arab nationalism as well. I pointed out after Trump’s inauguration that Zionism and antisemitism can actually be complementary processes because both—under the guise of wanting to sort people into the places they ‘come from’—contend that Jews really belong in Israel (i.e. not in the U.S., Egypt, or France). The founder of political Zionism, Theodore Herzl, saw this quite clearly, writing in his diary that, “The anti-Semites will become our most dependable friends, the anti-Semitic countries our allies.”

And you can see today how attacks on Jews in the diaspora are folded into a Zionist narrative that says Jews will never be safe anywhere they are a minority population, ergo Israel is an existential requirement for the continuation of the Jewish people. I can’t stress enough how many people believe this with every fiber of their being and embrace ever-more right-wing Israeli policies not because they possess some sort of deep antipathy toward Palestinians, but because they are certain that Jewish survival depends on it. Once you’re convinced yourself that another people represents an existential threat, there is nothing you won’t do and try to justify through the language of self-preservation. Yet, as far as I can see, the truly existential threat that Israel faces is not from without but from the messianic and Jewish supremacist forces within. As Gershom Scholem posed the question to Franz Rosenzweig nearly a century ago, “That sacred language on which we nurture our children, is it not an abyss that must open up one day?” I think that’s where we are today.

What is the two-state solution? Is it possible? Or, is a one-state solution the only realistic political possibility? What other possible outcomes do you see?

The two-state solution is the sacred cow of Middle Eastern politics, ostensibly the stated aim of countless countries and international bodies. But it is also a mirage, and I think honestly the conditions to realize it passed about twenty years ago though no one—least of all Democratic politicians—want to say that out loud (in this sense, the American right has been much more honest). Why is that the case? Well, there are about five times as many settlers in the West Bank now as when the Oslo Accords were signed, and settlements have been strategically established in between Palestinian population centers in order to prevent a geographically contiguous Palestinian state (Peace Now has great settlement stats and maps if you want to take a closer look). Given the extreme difficulty Israel encountered in dismantling the Gaza settlements in 2005—which only had about 8000 people—I see no way to do so on a much larger scale in the West Bank. This was always the goal: create ‘facts on the ground’ before any final political settlement was reached that would include Palestinian statehood. There are additional economic and environmental barriers we could speak about – which on top of the settlement pattern, in my eyes make the two-state solution more fantasy than actionable policy.

So why does everyone keep talking about it? Even now, in the midst of this awful war, one hears from the Biden administration, the UN, and regional players like Jordan, Egypt and Saudi Arabia that a renewed commitment to the two-state solution must follow the cessation of hostilities. It all feels pretty bad faith to me, a sort of diplomatic virtue signaling that one engages in while Israel proceeds with settlement and annexation. A single state is already the reality on the ground; the only matter to decide is what kind of state it should be. Here I’ll note that it’s encouraging to find this sober assessment gaining traction outside of lefty academic quarters. Anthony Cordesman of the Center for Strategic and International Studies—hardly an outpost of the Internationale—recently wrote that the “two-state solution may not be totally dead but is so close to death that efforts to revive it are likely to be little more than acts of zombie diplomacy.”

But we cannot, should not, underemphasize the challenges presented by the one-state alternative. First and foremost is 2022 polling that shows that support among Israelis and Palestinians for a single, democratic state (which in January earned endorsement from 20% and 23% of the population, respectively) is even lower than that afforded the two-state solution (which is supported by about one-third of each group). More Israeli Jews support an unequal one-state solution—i.e. the continuation and codification of present conditions—than the two-state solution, and 40% of Palestinians reported that their next step should be to “wage an armed struggle against the Israeli occupation” (26% of Israeli Jews hoped for “a definitive war with the Palestinians”). All the numbers are trending in the wrong direction if you hope to see a single, democratic, and peaceful country emerge from the present mess.

There is also the idea of a confederation, which would maintain separate states in terms of citizenship and institutions, but allow freedom of movement and extend permanent residency rights to Israelis in Palestine and vice versa along a European Union model, and involve extensive cooperation on economic, environmental, and security issues. The confederation model can be thought of as a sort of blended one and two state solution, and maybe it could gain traction (in the polling referenced above, it garnered support from 22% of Palestinians and 28% of total Israelis.) In fact, the Palestinian citizens of Israel are the only group that exhibits majority support for either a single democratic state of a confederation (I would happily put Sally Abed in charge).

Finally, I think it’s important to note that there is a lot of obfuscation around the one-state solution, but the details matter tremendously. I think it is crucial to recognize that Hamas does not desire a secular, democratic state but the inverse of Greater Israel – a fantasy of restoration and reversal of position, not justice. Any liberation worth its name can’t deliver another zero-sum game. We have seen with the history of Israel just how superficial freedom is when it is achieved at the expense of another.

How can we build Jewish community right now?

Now you have stumped me!

It’s very difficult, particularly for those of us who are in the tiny circle of Orthodox lefties. Our communities on the whole embrace positions that are at odds with our own, and it’s alienating. I find solace in conversations with individual friends or small groups who are similarly situated, but there isn’t a lot of space right now to have the sort of conversations that I think are necessary within mainstream Jewish communities. But maybe that will change in the future, and if so, we need to be ready to engage.

A lot of people aren’t sleeping. They feel the weight of anger, sadness and grief. For those asking, “What can I do?,” where who you point them?

Beta-blockers and melatonin! But also: walking outside, seeing people in person, backing away from the phones and infographics and picking up the books, donating to organizations that are doing essential humanitarian work, writing and calling elected officials, organizing and demonstrating in whatever way feels meaningful.

The last piece is the biggest part of the puzzle. I think there could be a really broad coalition of people who support Palestinian liberation but reject Hamas’s tactics, who reject both antisemitism and its weaponization, and who realize that a return to politics is the only way forward. But right now, some of the factors I outlined above are preventing such a coalition from emerging, and the loudest voices have come to mirror one another in their utter disregard for human suffering if it’s not on ‘their’ side. This might be one of the only true symmetries within a conflict that is fundamentally uneven in material terms.

I’d also add that in times of global crisis, we sometimes tend to neglect the local communities that need us. Get involved in local politics, make soup for a shelter, tutor kids who need extra help – these things don’t make the horror go away but they make us feel a bit less helpless than we do while doom scrolling.

Grief offers a different set of lessons, namely: that putting the world back together is impossible; that a true return of what was so horrifically lost is beyond human means; that there will never be a direct correspondence between what is just and what is achievable here on earth.

Finally, I think we should lean into the grief. Feeling the full magnitude of it helps to keep us human. I tend to intellectualize my feelings in order to make sense of the horrors I study, so this has been especially hard. But I’ve been thinking (gah!) more about grief because I’m currently saying kaddish for my father. It is hard to see grief as a positive emotion, but I have found it to be an interesting one. What grief represents, why it threatens to devour us, is a sense of loss that can never be made whole. Grief expresses the impossibility of reconciliation or restoration, of ever bringing things back to the way they used to be, and in that sense, is profoundly opposed to nostalgia. Perhaps ironically, grief can propel us forward by blocking the road back to some history or past experience.

I have thought about this frequently as the impasse between Israelis and Palestinians grows ever more formidable. Albeit in different ways, loss has been the experience of both peoples, and portions of both still fumble around longing for an impossible restoration. Grief offers a different set of lessons, namely: that putting the world back together is impossible; that a true return of what was so horrifically lost is beyond human means; that there will never be a direct correspondence between what is just and what is achievable here on earth. Grief requires first and foremost an acceptance of a loss that is both devastating and fundamentally uncurable. There is no going back, in short, and we need to reject any redemptive fantasy that is built upon the negation of the Other. “Much of the despair and pessimism that one feels at the whole Palestinian-Zionist conflict,” Edward Said wrote in 1979, “is each side’s failure in a sense to reckon with the existential power and presence of another people in its land, its unfortunate history of suffering, its emotional and political investment in that land, and worse, to pretend that the Other is a temporary nuisance that, given time and effort (and punitive violence from time to time), will finally go away.” Perhaps grief can compel us forward instead.

What are you reading right now? What reading would you recommend to people?

I just finished teaching my Brooklyn Institute class on Edward Said, which had been long scheduled for this fall and ended up being incredibly timely. There are so many works of his to recommend – but my favorites at present are the essays in the Peace and Its Discontents, Reflections on Exile, and Humanism and Democratic Criticism. My students also always love the interview he did with Ari Shavit in 2000.

If you want to understand more about the history, I always recommend Tom Segev’s One Palestine, Complete and Rashid Khalidi’s The Iron Cage (and other works) as a place to start. Also, there is a great compilation of early Zionist thought called The Zionist Idea edited by Arthur Hertzberg that should be required reading. Ditto for George Antonius’s 1938 classic, The Arab Awakening. The War for Palestine (edited by Avi Shlaim and Eugene Rogan) is an excellent collection of essays about 1948 and the aftermath. There are of course a ton of smart articles and essays floating around right now, but sometimes the experience of reading the news resembles being smacked in the head, and I think it’s actually most helpful to find your footing by looking at some of this scholarly work.

This history is both essential and, at a certain point, wearying, too over-burdened with contested meaning to do the work of true partisans. It is still vital to know, of course, but I find myself longing for visions of the future. In truth, the part of me who is not a professional historian, but is rather interested in the minimization of human suffering and the maximization of human freedom, has grown tired of the past.

I don’t think it is sound to place the whole blame on Israel. Ethnonationalism is a meaningless American catchword. Most scholars of nationalism reject the Kohn’s distinction between ethnic and civic nationalism nowadays.

As for the fact that Jews settled to a land inhabited by another people: Zionist thinkers invoked justifications: 1) They had nowhere else to go 2) Wealth redistribution (the Arabs who possessed a vast territory in the Middle East must share part of it the Jews who were a homeless people). The first justification is obviously stronger than the second but they both based on universal values.

North American liberal Zionists never talk about the peace plans rejected by the Palestinians in 2001, 2008 and 2014

As for Edward Said or Rashid Khalidi, they spent their entire lives distorting Zionism while left-wing Zionists such as Hertzberg and Amos Oz have tried to explain to Israelis and Jews that the Palestinian cause too was legitimate. This the other "asymmetrical" dynamics of this conflict.

Unfortunately, the current generation of liberal Zionists has joined the anti-Israel bandwagon. I won’t be part of it anymore. The Palestinians are not helpless victims and Israelis are not monsters wearing a human mask.

If this conflict is a clash of rights, the Palestinians too must do their share to understand Israelis and end the conflict. There is no self-criticism among the Palestinians. This is not healthy.

One last thing: those who think that the one-state solution is still an option after Oct. 7 live in a parallel world.