Tomorrow marks the anniversary of Hannah Arendt’s birthday. Hannah Arendt was born in Linden, Hannover, Germany on October 14, 1906.

I fell in love with Hannah Arendt in college, reading The Human Condition on a brown leather sofa in the library. I was wandering around the stacks on a Saturday afternoon looking for Erich Fromm’s Marx’s Concept of Man and found Hannah instead.

I think people have an image in their minds of Hannah Arendt as this very serious smoking figure bent over in thought. But one of the things I’ve learned writing a biography of Arendt is that she was incredibly vivacious. In the words of her first husband Günther Anders, she was “profound, cheeky, cheerful, domineering, melancholic, and always ready to dance.”

From an early age she was hungry for experience. She had a deep desire to understand the world that superseded any urge to make sense of it. And while she required solitude to think and write, she was also known for throwing raucous parties. She was the kind of woman who always opened a second bottle of wine and refused to quit smoking or eat healthy when the doctor told her she was going to die.

Arendt was demanding, unapologetic, and protective of her time. Reading her correspondence is a masterclass in dealing with bullshit: Asked for a syllabus, she says: “No, I’m not so orderly as to produce syllabi for my students. I’m busy enough trying to teach them.” Asked to review a theater script, she responds: “There must be some misunderstanding. I am not a literary critic, and I know absolutely nothing about the theater.” Invited to be on a panel with a historian who criticized her work, Arendt declares, “I hate to be so difficult, but I’m afraid the truth is that I am.”

It would be a shame to imagine Arendt only as a very serious woman writing about totalitarianism. Because just as much as we need inspiring authors to help us make sense of our contemporary political moment, we need a bit of levity to ground us as well.

One of my favorite stories about Arendt comes from Jerome Kohn, her literary executer. In an essay on the Bertolt Brecht controversy, he recounts an afternoon in Arendt’s apartment:

…At the mention of Brecht's name, her face lit up. She all but jumped from her chair, pulled up her skirts, showing her beautiful legs, and danced as she sang the first verse of the Moritat, the "murder" ballad with which Brecht and Weil's Three Penny Opera (1928) opens.

Arendt kept her private life to herself—the four walls of her home, her friends, which she lovingly called “the tribe”, her marriage with Heinrich Blücher—these were the spaces that nourished her solitude so she could enter the world as a public figure.

But there is more to Arendt than her public persona. There is also the Arendt that she has bequeathed us in her papers, correspondence, and poems left to the Library of Congress and the German Literature Archive. In there is the story of a woman who had a remarkable passion for living and led an extraordinary life. As she wrote in one poem:

I love the earth/As if traveling/to a foreign place,/and not otherwise./So life spins me/quietly on its thread/continuously, into unknown designs./Until suddenly, like the end of a journey—/the great silence breaks into the frame.

In our noisy world that demands constant attention, making it impossible to attend to anything, the story of Hannah Arendt’s life has given me something to hold onto in these dark times. And as much as she’s taught me about authoritarianism, fascism, and the dangers of fake news, she’s also taught me how to be alone with myself—how to attend to my solitude, protect my time, and how to say “no.” She’s taught me that no matter how chaotic things get, it’s okay to retreat from the public realm of appearances and turn off my email. She’s taught me that it’s okay to laugh, and sing, and dance.

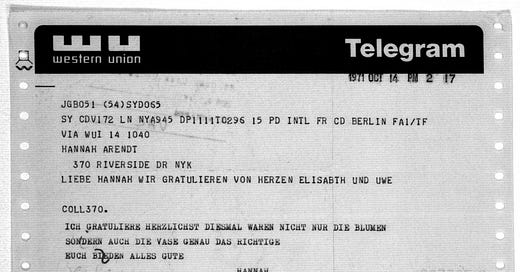

Take a little time on Hannah Arendt’s birthday to browse through her correspondence yourself: http://memory.loc.gov/ammem/arendthtml/mharendtFolderP02.html

Happy Birthday, Hannah.

-S

Thanks for the insights & the reminder that even as she was a powerful thinker and public persona, she was a unique person as well.

Wonderful commentary! I first met Hannah through Men in Dark Times in a European Political Theory course at UT Austin in the very early 1970s. I was hooked and have proceeded to read pretty much everything over the years.