Dear Reader,

I’ve been thinking about ends lately. More precisely, how Hannah Arendt concludes her work. As I was writing the biography I began to notice that like many writers she has a tick. (Well, she has many but that’s for another post.) She likes to end on a note of well-tempered optimism, often returning to Augustine or Cato quoting Cicero.

Which is surprising because Arendt is not an optimistic thinker. At the end of The Human Condition, she is not hopeful that freedom can be saved in the modern world. On Revolution ends with a lament that the American Revolution failed to find a way to preserve the spirit of revolution in political institutions. Eichmann in Jerusalem ends with a death sentence.

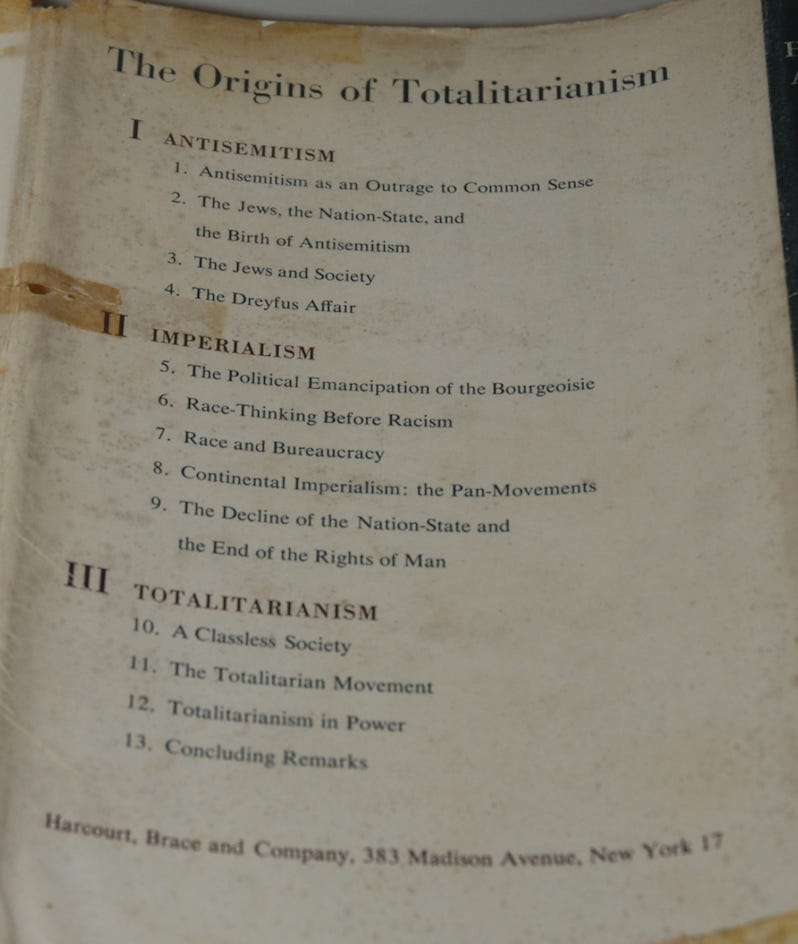

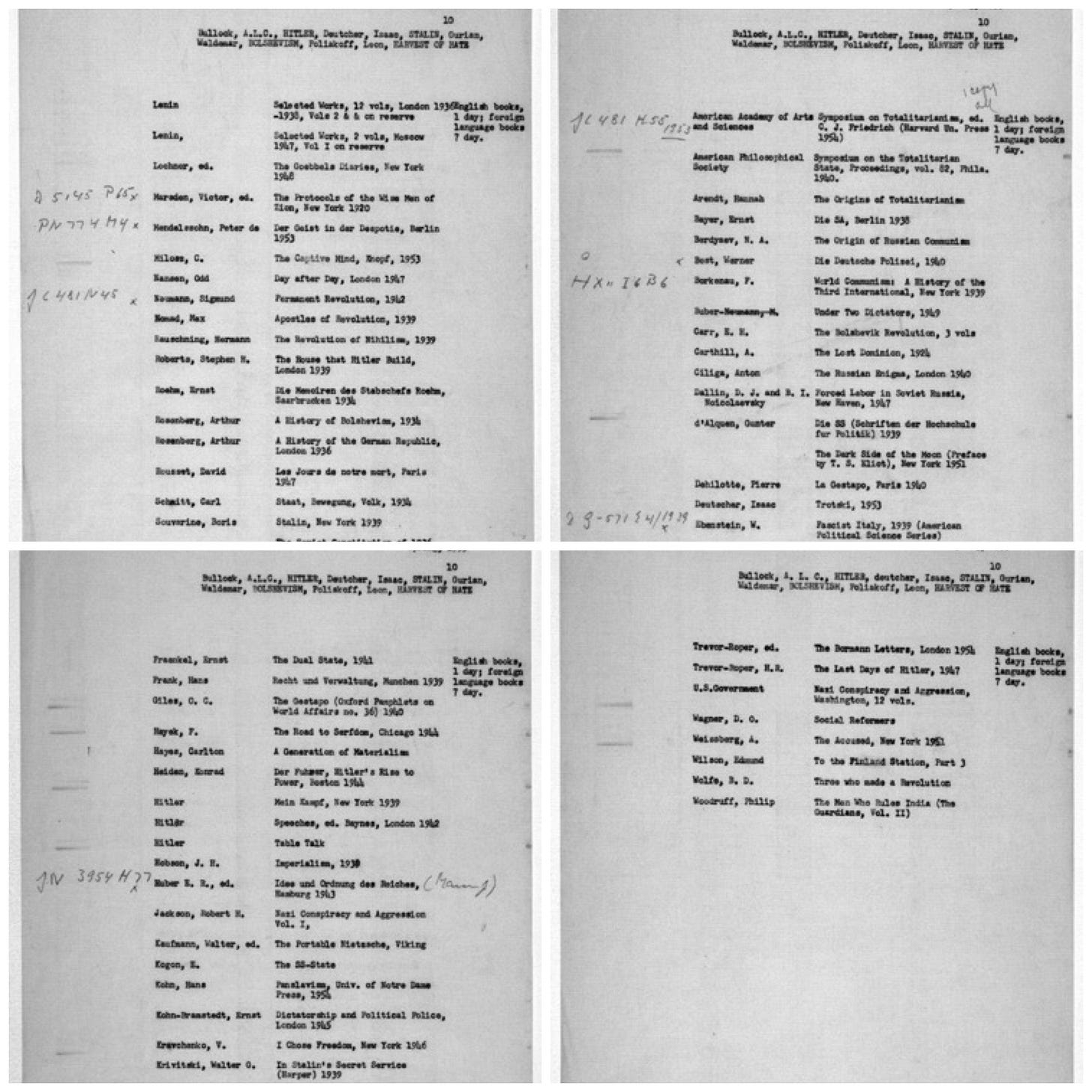

Then there is The Origins of Totalitarianism. Next to The Life of the Mind it was Arendt’s most ambitious undertaking. And there is not one end for Origins, there are three. Hannah Arendt wrote three distinct conclusions for The Origins of Totalitarianism between 1951 and 1958.

During her life, Arendt published Origins in several formats. (That could be another post in itself.) But there are three distinct conclusion for the three editions she oversaw in English.

The first edition published in 1951 ends with the chapter titled “Totalitarianism in Power” and includes a conclusion titled, “Concluding Remarks.” In the second edition published in 1958, Arendt deleted the first conclusion and included two additional chapters titled “Ideology and Terror” and “Epilogue: Reflections on the Hungarian Revolution.” In later published editions, “Concluding Remarks” and the final chapter on the Hungarian revolution were deleted altogether. Unless you’re reading the 2004 edition which includes an “Appendix”, which includes “Concluding Remarks” and an essay from 1958 titled, “Totalitarianism.”

Point being, depending on which edition you happen to pick up at your local used bookstore, you are in for a very different reading experience. The three distinct endings leave the reader with dramatically different impressions of Arendt’s stance toward totalitarianism, freedom, and the future.

Conclusion #1 (The original, now deleted conclusion from 1951):

When Hannah Arendt pitched her manuscript in the late fall of 1943 the war was still ongoing. She wrote as she read and changed the outline of her book as new information became available. By the time she finished a first draft in 1949, Hitler was dead, but Stalin was still alive. The final chapter on “Totalitarianism in Power” ends with a forewarning that the elements of totalitarianism will continue to exist in the world:

Totalitarian solutions may well survive the fall of totalitarian regimes in the form of strong temptations which will come up whenever it seems impossible to alleviate political, social, or economic misery in a manner worthy of man.

The conclusion to the first edition of The Origins of Totalitarianism was deleted from subsequent editions. It was titled “Concluding Remarks” and Arendt described it as “consciously inconclusive.” One of the issues she wrestled with while writing was the changing state of totalitarianism itself, as new information became available. She was unhappy with the word “origins” in the title, and thought the book would need to be revised at least every seven years.

The original, now deleted conclusion reads:

For those who were expelled from humanity and from human history and thereby deprived of their human condition need the solidarity of all men to assure them of their rightful place in ‘man’s enduring chronicle.’ At least we can cry out to each one of those who rightly is in despair: ‘Do thyself no harm; for we are all here.’ (Acts, 16:28)

Conclusion #2 (The conclusion to the revised and expanded 1958 edition, deleted in subsequent printings):

In the revised and expanded 1958 edition, Arendt included two new chapters, “Ideology and Terror,” “Epilogue: Reflections on the Hungarian Revolution.” These sections were later retracted after more information about the Hungarian Revolution and workers’ councils became available.

The 1958 conclusion reads:

Still, the danger signs of 1956 were real enough, and although today they are overshadowed by the successes of 1957 and the fact that the system was able to survive, it would not be wise to forget them. If they promise anything at all, it is much rather a sudden and dramatic collapse of the whole regime than a gradual normalization. Such a catastrophic development, as we learned from the Hungarian revolution, need not necessarily entail chaos—though it certainly would be rather unwise to expect from the Russian people, after forty year of tyranny and thirty years of totalitarianism, the same spirit and the same political productivity which the Hungarian people showed in their most glorious hour.

In a short reflective essay written for The Meridian, on the occasion of the publication of the revised edition, Arendt reflects on her new conclusion:

Thus, the last chapter of the present edition is an Epilogue or an afterthought. I am not at all sure that I am right in my hopefulness, but I am convinced that it is as important to present all of the inherent hopes of the present as it is to confront ruthlessly all its intrinsic despairs. In any event, to a political writer, this must be more important than to present the reader with a well-rounded book.

Conclusion #3 (The end of the book as it stands today after Arendt retracted her writing on the Hungarian Revolution):

When Arendt deleted the original conclusion, the additional chapter on the Hungarian Revolution, she let “Ideology and Terror” stand as the new end to the work.

The end of “Ideology and Terror” reads:

But there remains also the truth that every end in history necessarily contains a new beginning; this beginning is the promise, the only “message” which the end can ever produce. Beginning, before it becomes a historical event, is the supreme capacity of man; politically, it is identical with man’s freedom. Initium ut esset homo creatus est— “that a beginning be made man was created” said Augustine. This beginning is guaranteed by each new birth; it is indeed every man.

Even in 1958, Arendt thought this was the appropriate end for her book even though it was the penultimate chapter. In “Totalitarianism” she describes her frustration with the 1951 conclusion:

The book originally ended with certain suggestive but consciously inconclusive ‘Concluding Remarks’ that are now replaces with a much less suggestive and more theoretical chapter on ‘Ideology and Terror: A Novel Form of Government.’ This chapter seemed to me the book’s paper conclusion; but from a more aesthetic viewpoint, it may be argued that the very inclusiveness of the original ending, showing the extent to which the author was involved and prepared to remain engaged in her subject matter, was better attuned to the mood and style of the whole book.

One might argue the variable endings reflect a core value at the heart of Arendt’s work: there is no end in thinking. Any work relying so heavily on contemporary events, as she said, needs constant revision.

Arendt was unhappy with “origins” because it seemed to imply the origins of totalitarianism could be located somewhere. When she translated The Origins of Totalitarianism into German she retitled it Elemente und Ursprünge totaler Herrschaft. Antisemitismus. Imperialismus. Totale Herrschaft (Elements and Origins of Total Dominion. Antisemitism. Imperialism. Total Domination). Not even the title could be fixed in time.

I can’t help but wonder what chapters and conclusions Arendt might write today.

Yours,

Sam

Great how you handle the topic. For this 3 ♥️♥️♥️ - For clarity in a nutshell - For completeness to the case - For Beauty, of course. - And one more, because you also leave your end open. ♥️ Thank you.

Act16:28 “But Paul cried with a loud voice, saying, Do thyself no harm: for we are all here.”

Questions in the midst of despair with a brief light of eschatological hope but remaining in the world “What must I do to be saved?” making all things new - the death for a new birth.

Initium ut esset homo creatus es - “that a beginning be made man was created" Augustine ‘City of God’ BookXII Chap.20,”…its deliverance from misery is something new, since, by their own showing, the misery from which it is delivered is itself, too, a new experience.” The new beginning where the first man was created (Adam - Everyman).To create new things never before created.