20 Tuesdays

Lesson #1: Totalitarian movements are mass organizations of atomized, isolated individuals.

Dear Reader,

In 2016 Hannah Arendt’s The Origins of Totalitarianism (1951) became a bestselling book. That winter I began teaching Origins to adults in New York City through the Brooklyn Institute for Social Research who had purchased Arendt’s nearly five-hundred page work in an attempt to understand what was happening in American politics.

As we barrel toward another election, facing another possible Trump victory, I wanted to create a space for people to come together.

Thinking back on the past ten years of teaching Origins, I’ve made a list of the most important lessons from Arendt’s work that students return to time and again. So, every Tuesday from now until November 5th, I will share one lesson with you.

It’s my hope that this newsletter might serve as a prompt for curious readers. For me, Arendt’s work has always been a springboard, never an end in itself. If totalitarianism—or something akin to it—appears in the United States today, we are going to need new voices, new vocabularies, to carry us forward. This is just one place to begin.

Please share!

Until soon,

Sam

Lesson #1: Totalitarian movements are mass organizations of atomized, isolated individuals.

Key quotes:

Totalitarian movements are mass organizations of atomized, isolated individuals.

The chief characteristic of the mass man is not brutality and backwardness, but his isolation and lack of normal social relationships.

What prepares men for totalitarian domination in the non-totalitarian world is the fact that loneliness, once a borderline experience usually suffered in certain marginal social conditions like old age, has become an everyday experience.

Core idea:

When Hannah Arendt revised The Origins of Totalitarianism in 1958, she argued that a feeling of abandonment was the underlying condition of all totalitarian movements. It is not just feeling alone in the world, but feeling abandoned by the world that leads to feelings of isolation. And when one feels isolated, one is unable to move. This is the attraction of a movement, it gives an isolated individual something to belong to where they can feel a sense of purpose and meaning.

How it happens:

Masses are mobilized by political propaganda.

Political propaganda atomizes individuals into masses by uniting them with intentional ideology instead of common interests: my neighbor and I both like to find wildflowers; I like playing soccer; there’s a virtual reality game I play with my daughter who likes video games.

Isolated masses of people are held together by a common belief that they are right, and that the others (who exist outside the ideology) are wrong.

Those susceptible to isolation and atomization are those who feel like their interests have been abandoned by the political parties, their local communities, and organizations.

Relevance for today:

Identifying individuals who feel isolated

The signs of isolation might be counter-intuitive. Isolated people don’t always keep to themselves.

Loneliness has become nearly synonymous with isolation today, and isolated individuals often have trouble connecting with others, even though they often seek out company. When an isolated individual finds someone to listen to them they tend to talk compulsively, ask fewer questions of the person they’re engaging, and have difficulty carrying on the flow of conversation. It’s possible that they are trapped in a isolation-loneliness loop and are not sure how to find a way out.

The isolation-loneliness loop goes something like this: I feel isolated, I meet someone to talk with, I overshare, I talk excessively, and I express little interest in the other person, which pushes the other person away; I leave feeling even more isolated, and have reinforced the belief that I am alone. This belief will make it harder for me to reach out in the future and trust that I can form a meaningful connection with others. I might become suspicious, cynical, and find myself constantly doubting other people’s intentions.

Two suggestions for getting out of the isolation-loneliness loop:

If you find yourself in a conversation with a person who is feeling isolated what they often need is to know that you hear them. It’s not about agreeing or disagreeing, it’s about listening. And listening is not about scoring points, or saying the right thing. It’s about being present. Notice the couple in Edward Hopper’s painting above. The man is leaning forward, his shoulders are caved in, he is looking down at a newspaper. The woman is physically turned away from him, she is looking down, her arm rests on the piano across her body. They are literally closed off to one another and separated by a table.

Feeling heard is one of the, if not the, most powerful forms of recognition that we can offer to another person. Being present, when one is able, allows us to turn toward one another, make eye contact, and physically face the other openly. One trick for making a person feel like you hear them is by mirroring their language back to them. Even if you want to disagree with a point they’re making, use they’re language. Begin your sentence by repeating what they’ve just said. Another trick is using the first law of improv: “Yes, and…”. This way you build a conversation together, instead of mimicking two pool balls knocking into one another.

If you recognize yourself caught in an isolation-loneliness loop, know first of all that you are not alone in feeling isolated. Many people feel isolated today, afraid to share their opinions and ideas with strangers and loved ones. The fastest way to feel connected to other people is to do something nice for somebody else. This is hard because when a person feels isolated the voice inside their head often says: “But why can’t anyone think about me! Why don’t they realize I’m right! Why do I always have to be the one doing something for others?” If you catch yourself thinking something like this, try a random act of kindness, or picking up the phone and just listening to a friend. It’s the action in-itself that generates movement.

The trick to feeling heard is learning to listen.

By the age of 40 Americans will have spent most of their life alone. And in that alone time they watch on average 3 hours of television per day and spend on average of 7 hours per day online.

Questions for conversation:

On my very worst day how would I talk to a difficult person?

On my very best day how would I talk to a difficult person?

Is there someone I can reach out to today, just to listen?

Thank you for reading!

Next week: Laying the groundwork for the systematic destruction of reality.

Until Tuesday,

Sam

From the archive:

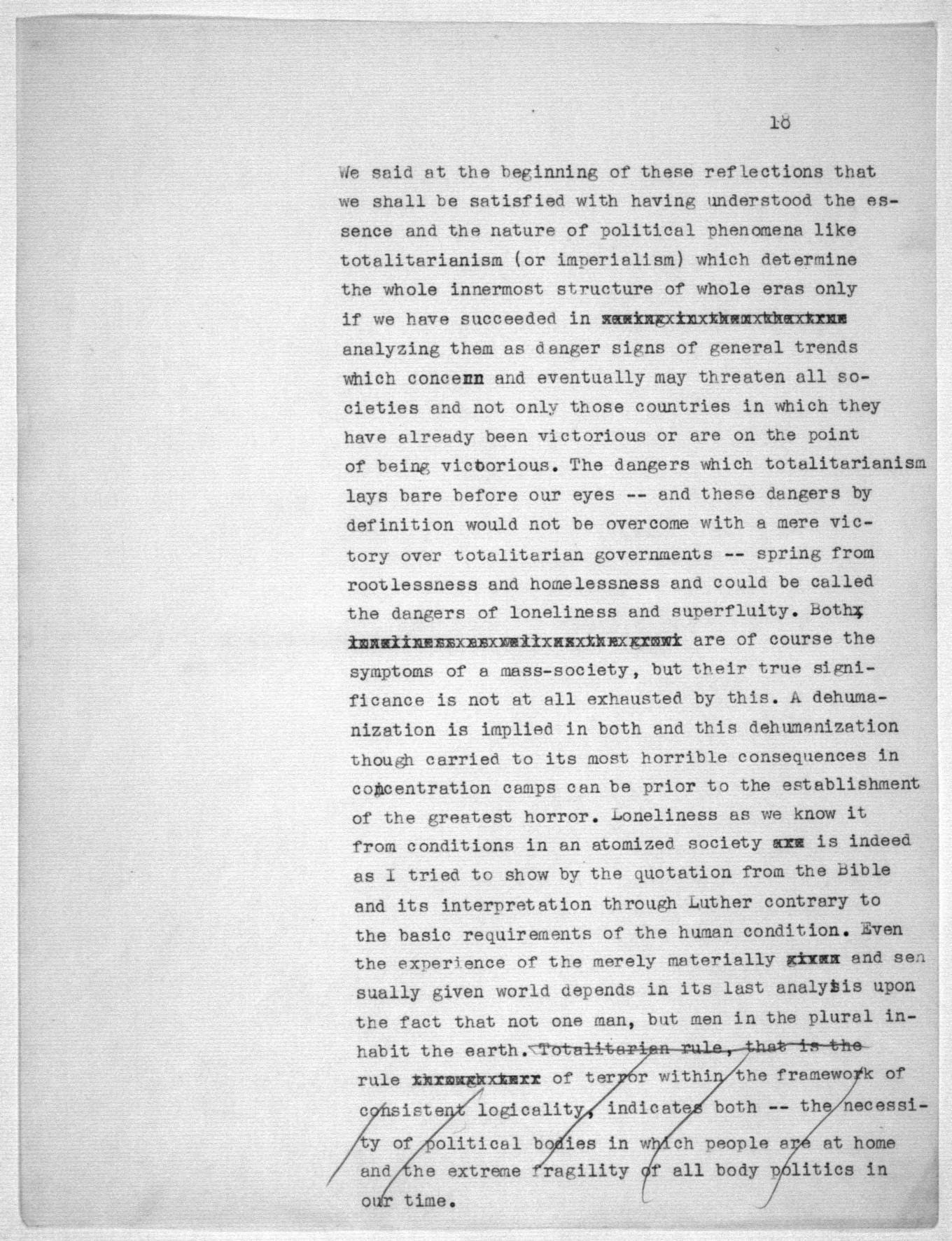

A page from “On the Nature of Totalitarianism” dealing with loneliness.

Comme toujours, Arendt nous aide à penser au-delà de ce qui nous est présenté. Merci Sam pour cette initiative.

Yes to all that—and this one seems to be going around the globe (far right mvmt). I hope we’re not caught in it coz we’re supposed to be the beacon of liberalism and freedom…with that said as a writer I’m curious about the next topic!

Thanks for sharing.